Anyone that’s ever worked for a software company (or any organization that works to firm deadlines) has probably experienced a “death march”. It’s the mission-critical project that seems to be constantly in crisis; the one that consistently requires overtime and all-nighters to meet milestones; the one in which team members start to turn on each other or drop like flies due to stress and overwork.

Sometimes great things are achieved through heroic effort but always the doubt lingers; surely there must be a better way?

Having been on the unpleasant management side of such a project recently (i.e. I was the bastard holding the whip), I decided to do some research to answer this question.

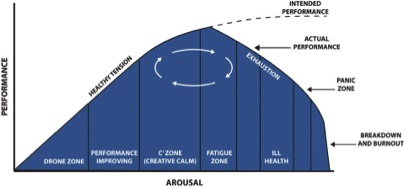

Not surprisingly, finesse and sensitivity are required to maintain the right level of “arousal” (ie. external pressure) within an individual, team or organization, to achieve the maximum level of performance. The following curve (a variation of the Yerkes-Dodson Law) illustrates it well:

Too little pressure and your team’s not working hard enough. More pressure yields improved performance up to a point. Too much pressure leads to exhaustion and declining results. To maintain maximum performance at the peak of the curve you must actually cycle between the higher pressure “fatigue” zone and the slightly lower pressure “creative calm” zone.

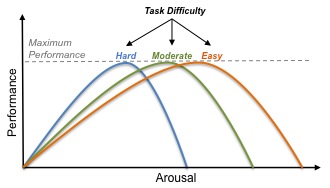

The tricky thing about this human performance function isn’t just that it’s hard to manage the right cycle of pressure to achieve peak performance, it’s that the right amount also depends on the difficulty of the task.

For easy tasks, more external pressure is required to achieve maximum performance while for complex tasks, less external pressure is optimal.

Here’s a silly example: being chased by a lion (external pressure) will certainly help you run faster (an easy task) while it’s unlikely to help you do math calculations more accurately (a tougher task). Most of what we ask professionals and skilled workers to do falls into the “more difficult” territory (though some things are tougher than others).

Now, think about companies you know. Many probably exist comfortably on the left side of the performance curve and could benefit from the application of some healthy tension. Others always seem to be in crisis (often of their own making). They work their exhausted employees like prisoners in a gulag but their results never really improve.

It’s the companies we admire, the ones with unstoppable growth buoyed by the energy and enthusiasm of their employees, that seem to have mastered the human performance function. They work hard, play hard and deliver results.

Think about that the next time you’re cracking the whip (I know I will).

This article was published more than 1 year ago. Some information may no longer be current.